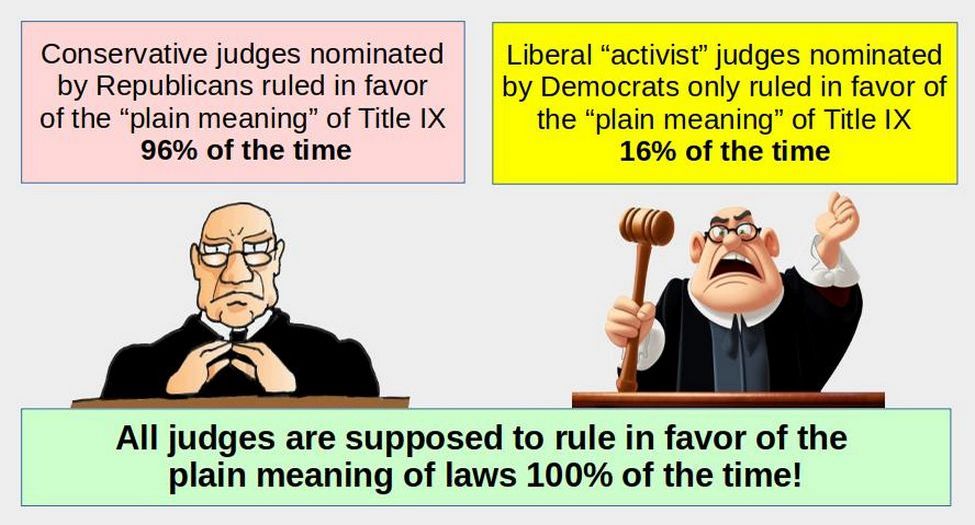

It has been claimed that the Washington Supreme Court has a “double standard” on deciding whether or not an Initiative complies with the Washington State Constitution. Before we begin, I want to note that I have written articles providing a mountain of evidence on the double standards in our federal courts. Here is a link to one of these articles on liberal federal courts, such as the Ninth Circuit, grossly misinterpreting the plain meaning of Title IX.

I have also written articles critical of the Washington State Supreme Court. So I am open to considering the claim that our State Courts are biased. However, if we are going to make this claim, we need to provide evidence that this claim is true. In this article, we will use two recent Washington Supreme Court rulings in favor of liberal Initiatives that were found to be constitutional to determine if this claim of a double standard on Initiatives is true. The first example is a case on a 2003 Initiative. The second example is a case on a 2012 Initiative.

Example #1: Citizens for Responsible Wildlife Mgmt. v. State, 149 Wn.2d 622, 630, 71 P.3d 644 (2003)

Citizens for Responsible Wildlife Management v. State refers to a Washington State Supreme Court case concerning the legality of initiative I-713 passed by the voters in 2000 that restricted certain hunting and trapping practices. The case focused on whether these initiatives violated the state's public trust doctrine, which holds that the state manages natural resources for the benefit of the public. The court ultimately upheld the initiatives, finding that the state had not relinquished its control over wildlife management and therefore did not violate the public trust doctrine.

Here is a link to this Washington Supreme Court decision:

https://law.justia.com/cases/washington/supreme-court/2003/72186-6-1.html

Here are quotes from this decision:

“Citizens for Responsible Wildlife Management, on direct review to this court, claim that Initiative 713 violates Washington Constitution article II, sections 19 and 37. Finding that appellants have not shown, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Initiative 713 violates the constitution, we affirm the superior court's denial of the summary judgment motion.”

“Citizens contend that initiatives should be given less deference than legislatively enacted bills, when reviewing for constitutional infirmities, because initiatives result from a "closed process" where "the initiative proponents are comprised of a small group of people."

“This court was clear in Amalgamated Transit Union Local 587 v. State that statutes enacted through the initiative process must be shown to be unconstitutional beyond a reasonable doubt; they are not reviewed under more or less scrutiny than legislatively enacted bills…. Any reasonable doubts are resolved in favor of constitutionality. Wash. Fed'n, 127 Wash. 2d at 556, 901 P.2d 1028. Citizens must meet the same burden in proving I 713's unconstitutionality as they would for any other statute.”

“Citizens argue that the title is restrictive and violates section 19 because it impermissibly contains two subjects, trapping with body-gripping traps and killing with poisons. The State and Sponsors argue that the title addresses the single subject of humane treatment of animals, that the title is therefore general, and they respond that the title does not impermissibly deal with two subjects.”

“A more moderate interpretation, as compared to those offered by the parties, is that the title deals with banning methods of trapping and killing animals. Using the above quoted examples of general and restrictive titles to guide the determination here, I-713's title is general. I-713's title contains specific topics as well, namely, body-gripping traps and pesticides. As in Amalgamated, however, those topics are merely incidental to the general topic reflected in the title a ban on methods of trapping and killing animals. The title for I-713 is most accurately described as general and does not contain two subjects.”

“However, even if we assume, arguendo, that the title is restrictive, it is still a constitutionally valid title. The subjects of trap and pesticide use for animals are related so as not to be the individual, disjointed subjects that Citizens contend they are. The provisions in the initiative governing the types of traps and pesticides that may be used are fairly within the subject expressed in the title.”

“Citizens argue that there is no rational unity between banning body-gripping traps and the use of the pesticides because "it is completely unnecessary to ban traps in order to implement the ban on the use of these chemical compounds as pesticides… They claim that the initiative "manifests the evils" of logrolling, presumably by forcing voters to vote, in combination, on whether to ban certain traps as well as the pesticides.”

“Citizens misconstrue the analysis in Amalgamated. The language upon which Citizens deduce their "test" reads as follows: “there is no rational unity between the subjects of I-695… I-695 also has two purposes: to specifically set license tab fees at $30 and to provide a continuing method of approving all future tax increases. Further, neither subject is necessary to implement the other. I-695 violates the single-subject requirement of article II, section 19 because both its title and the body of the act include two subjects: repeal of the MVET and a voter approval requirement for (future) taxes. “

“An analysis of whether the incidental subjects are germane to one another does not necessitate a conclusion that they are necessary to implement each other, although that may be one way to do so. This court has not narrowed the test of rational unity to the degree claimed by Citizens…. the statements made in Amalgamated and City of Burien in regard to the dual subjects being unnecessary to implement the other were made to further illustrate how unrelated the two were.

“Article II, section 37 provides that "no act shall ever be revised or amended by mere reference to its title, but the act revised or the section amended shall be set forth at full length." The purpose of section 37 is to "protect the members of the legislature and the public against fraud and deception; not to trammel or hamper the legislature in the enactment of laws." An act is exempt from section 37 requirements if the act is complete, independent of prior acts, and stands alone on the particular subject of which it treats. "Nearly every legislative act of a general nature changes or modifies some existing statute, either directly or by implication" but this, alone, does not inexorably violate the purposes of section 37. "Undoubtedly, modification of existing laws by a complete statute renders the existing law by itself `erroneous' in a certain sense." Only that part of an act that violates section 37 will be invalidated, provided there is a severability clause. See Amalgamated, 142 Wash. 2d at 256, 11 P.3d 762.”

“An act is amendatory in character, rather than complete, if it changes the scope or effect of a prior statute, and therefore must comply with section 37. First, the court must determine whether the bill is such a complete act that the scope of the rights created or affected by the bill can be ascertained without referring to any other statute or enactment. Id. Second, would a determination of the scope of the rights under the existing statutes be made erroneous by the bill? “

“Qualifications of that two-part test have subsequently been made. This court, in Amalgamated, cautioned against too broad of an analysis for section 37 violation and clarified that "[a] later enactment which is a complete act may very well change prior acts and yet still be exempt from the requirement of article II, section 37."

“Complete acts which (1) repeal prior acts or sections thereof on the same subject, (2) adopt by reference provisions of prior acts, (3) supplement prior acts or sections thereof without repealing them, or (4) incidentally or impliedly amend prior acts, are excepted from section 37.”

“The first prong of the test is satisfied, i.e., the scope of the rights created or affected by I-713 can be ascertained without referring to any other statute or enactment.”

“As to the second prong, Citizens vie for a strict interpretation of section 37 and its requirements, contending that I-713 fails because it does not set forth statutes that it amends. In so doing, Citizens do not argue their point in light of the second prong of the section 37 test as put forth in Amalgamated, above. Instead, they argue that I-713 creates ambiguity as to RCW 77.36.030 in three ways, leaving a landowner who reads RCW 77.36.030 unaware of what his rights are regarding trapping problem animals.”

“I-713 does not change a landowner's right to trap; it regulates the types of traps that may be used. In this way, the initiative does not alter preexisting rights or duties to an impermissible degree… the change I-713 makes to the licensing requirements of landowners and we find that that change is not of constitutional magnitude.”

“while RCW 77.36.030 goes to whether problem animals may be killed or trapped at all, I-713 imposes incidental restrictions on the manner in which they may be killed or trapped. As such, we hold that RCW 77.36.030 and I-713 are not aimed at the same subjects and, thus, I-713 stands alone on the particular subject of which it treats and therefore does not violate section 37.”

Conclusion from the first example

The above decision was 8 to 1 with Justice Sanders dissenting. Sanders essentially argued that the ruling resulted in a lack of clarity about when the Single Subject rule was violated. But I can not see a lack of clarity. I can see that the two Eyman subjects were not even remotely related while the two trapping subjects were directly related. So I think this judge made a reasonable decision.

Example #2: Wash. Ass’n for Substance Abuse & Violence Prevention v. State, 174 Wn.2d 642, 652, 278 P.3d 632 (2012)

I-1183 removed the State from the business of distributing and selling spirits and wine, imposes sales-based fees on private liquor distributors and retailers, and provides a distribution of $10 million per year to local governments for the purpose of enhancing public safety programs. Upon review of the matter, the Supreme Court held that the Appellants Washington Association for Substance Abuse and Violence Prevention, Gruss, Inc. and David Grumbois did not overcome the presumption that the initiative was constitutional, and therefore the affirmed summary judgment in favor of the Initiative.

Here is a link to a PDF of the Washington Supreme Court 2012 29 page ruling:

https://cases.justia.com/washington/supreme-court/87188-4-1.pdf?ts=1396151904

Here are quotes from this ruling:

“This court was asked to determine whether Initiative 1183 (I-1183) violates the single-subject and subject-in-title rules found in article II, section 19 of the Washington State Constitution. “

“Appellants contend that I-1183 contains multiple subjects,in violation of article II, section 19’s single-subject rule. Additionally, appellants claim that I-1183’s multiple subjects were not all expressed in the ballot title of the initiative, in violation of article II, section 19’s subject-in-title rule.”

“The parties agree that the ballot title is general, and we find so as well. I- 1183’s title indicates that it generally pertains to the broad subject of liquor. There is no violation of article II, section 19 even if a general subject contains several incidental subjects or subdivisions.”

Appellants argue that the challenged provisions lack rational unity with the general topic—which they characterize as “‘liquor privatization’”—and with one another. Appellants contend that I-1183 violates the single-subject rule because along with the general topic of liquor privatization, the initiative includes a $10 million public safety earmark, privatizes wine distribution, impacts liquor advertising, and modifies the State’s policy regarding liquor.

“Turning first to the public safety earmark, this provision is germane to the general topic of I-1183, whether that is liquor or the narrower subject of liquor privatization”

“Moreover, the legislature’s recognition of the relationship between liquor regulation and public welfare supports our finding that these issues share rational unity.”

“I-1183’s provision of funds for public safety actually has a closer nexus to the subject of liquor than does the general revenue provision that has existed since the State began regulating liquor.”

Any “‘objections to the title must be grave and the conflict between it and the constitution palpable before we will hold an act unconstitutional.’

“Intervenors rely on Kreidler v. Eikenberry, 111 Wn.2d 828, 834, 766 P.2d 438 (1989), in which this court refused to review the ballot title decision of a superior court and noted that “the public interest is served by finality in this matter.” Kreidler is inapposite to this case, however, as appellants do not challenge the result of the ballot title determination, but rather the constitutionality of the law itself. Intervenors’ interpretation of Kreidler and analogous cases would improperly constrain any constitutional challenge to initiatives to the expedited process of ballot title adjudication.”

“The phrase “license fees based on sales” is sufficient to indicate to an inquiring mind the scope and purpose of that provision of I-1183. The challenged portion of I-1183’s ballot title is not palpably misleading or false.“

Example #2 Conclusion

This decision was unanimous. There was no dissent. I also do not see any problems with this decision.

Challenge to Provide an example

So far, I have not found an example to support the claim that there is a double standard for conservative initiatives. Instead, I think the Washington Supreme Court has been fairly consistent on this issue. If folks want to continue to contend that there is a double standard, they should provide at least one example to support their claim.